- Have any questions?

- [email protected]

PERSUASION ARCHITECTURE

Leveraging Psychology in Digital Marketing

November 25, 2023

EMOTION-DRIVEN BEHAVIOR

November 26, 2023Marketers can also use implicit directional cues, such as line of sight. An eye tracking study performed by Neuromarketing suggests that our brains process visual cues incredibly quickly, especially in comparison to text. This is supported by the discovery of the Triune brain, in the 1960’s, by neuroscientist Paul D. MacLean who identified that there are 3 main parts to the brain:

1. The Human (new)—responsible for language, learning, conscious thoughts and our personalities

2. The Mammalian (middle)—deals with our moods, emotions and hormones.

3. The Reptilian (old)—in charge of our most basic survival functions—eating, breathing and fight-or-flight reactions.

Significant research by Christophe Morin has discovered that the “old” brain is actually responsible for driving buying decisions and that it tends to be initially engaged by imagery more than text.

![]()

Using eye-tracking technology, usability specialist James Breeze conducted a study about how humans instinctively examine images. This Australian study, conducted by Usableworld.com.au, consisted of 106 people looking at Figures 2 and 3 for the same amount of time (the images were shown in a random order and tracked with a Tobii T60 eye tracker).

Humans are naturally drawn to other human faces, and because of this, in both versions of the advertisement, a buyers’ initial gaze is likely to land on the baby’s face.

Keeping that in mind, you will understand why in Figure 2, the positioning of the baby’s face actually draws a viewers’ eye away from the marketing message. The heat map illustrates this with the focus of attention highlighted in orange and red over the baby’s face, and yellows and greens, indicating less attention, over the actual message.

But, in Figure 3, when the baby’s face is turned toward the marketing message, there is a significant amount of red and orange over the messages, indicating that the text was read.

These examples illustrate that while images are an incredibly powerful part of our marketing messages, they have the ability to work against marketers if basic psychology principles are ignored.

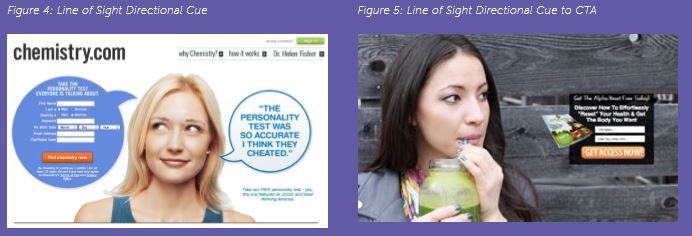

In another example, Figure 4 uses a line of sight directional cue to guide the viewer to the main objective of the page—the personality test that matches users with one another.

Figure 5 also uses line of sight to guide the reader’s attention—this time, directing them to a data capture form.

By grasping the principles of persuasion marketers can help buyers achieve their objectives while also achieving their own. Marketers and buyers benefit from communications designed to direct viewers toward the task marketers want them to complete.